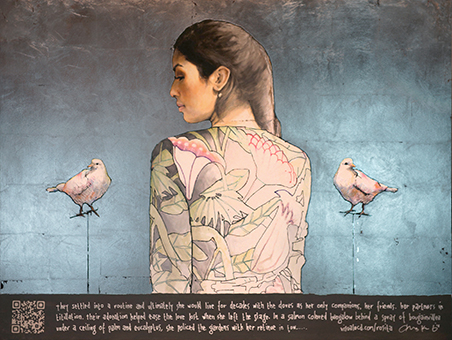

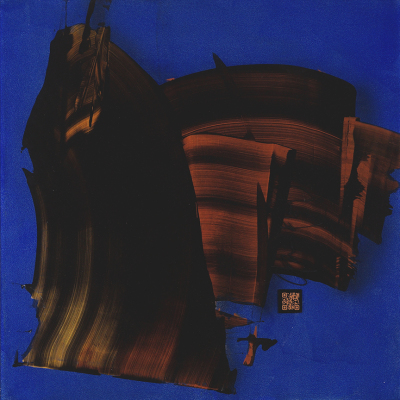

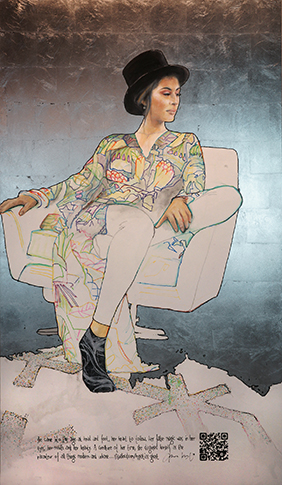

Hypatia’s Ghost;

A plausible story

40″ x 75″

Mixed Media on Wood Panel

GPS 38.071097, -122.529782

Date 2.01.2018

Myra Pantoja for the modeling

She came into the age at head and foot, her heart to follow.

Her false magic was in her eyes, her mouth and her beauty.

A creature of her time, the first Valkyrie to arrive mid-century,

she disguised herself as the raconteur of all things modern and urbane.

With roots anchored in Alexandria and Rome,

her true magic was premeditated

and always employed in service of her mission.

She was committed to the spread of unconditional love,

giving no quarter to practitioners of anything less.

Under her breath, she sang a song not yet written.

Are you thirsty?

I bring water

Can you see me?

Call me daughter.

Are you hungry?

I will feed you

Are you naked?

I bring clothes

I’m your mother

and your father

your sister

and your brother

I don’t know you

but I feel you

Can you see me?

Can I love you?

Notes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypatia#20th_century

Hypatia, a Hellenistic Neoplatonist philosopher, astronomer, mathematician, and inventor,[6] who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, then part of the Eastern Roman Empire.[7] She was the head of the Neoplatonic school at Alexandria, where she taught philosophy and astronomy

20th century

An actress, possibly Mary Anderson, in the title role of the play Hypatia, c. 1900

In the 20th century Hypatia’s life and death was cast in the light of women’s rights and she was adopted by feminists.[156] The author Carlo Pascal claimed in 1908 that her murder was an anti-feminist act and brought about a change in the treatment of women, as well as the decline of the Mediterranean civilisation in general. Dora Russell, the wife of Bertrand Russell, published a book on the inadequate education of women and inequality with the title Hypatia or Woman and Knowledge in 1925.[16] The prologue explains why she chose the title:[16] “Hypatia was a university lecturer denounced by Church dignitaries and torn to pieces by Christians. Such will probably be the fate of this book.”[16]

Hypatia’s death became symbolic for some historians. For example, Kathleen Wider proposes that the murder of Hypatia marked the end of Classical antiquity,[157] and Stephen Greenblatt observes that her murder “effectively marked the downfall of Alexandrian intellectual life”.[158] On the other hand, Christian Wildberg notes that Hellenistic philosophy continued to flourish in the 5th and 6th centuries, and perhaps until the age of Justinian I.[159][160]

The thirteenth and final episode of Carl Sagan’s 1980 PBS series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage relates a heavily fictionalized retelling of Hypatia’s death, which results in the “Great Library of Alexandria” being burned by militant Christians.[107] In actuality, though Christians led by Theophilus did indeed burn the Serapeum in 391 AD, the Library of Alexandria had already ceased to exist in any recognizable form centuries prior to Hypatia’s birth.[161]

As an intellectual woman, Hypatia became a role model for modern intelligent woman[156] and two feminist journals were named after her:[156] the Greek journal Hypatia: Feminist Studies was launched in Athens in 1984,[156] and Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy was launched in the United States in 1986.[156] In the United Kingdom, the Hypatia Trust has compiled a library and archive of feminine literary, artistic and scientific work since 1996.[16] An extension of the trust has established the Hypatia-in-the-Woods retreat in Washington State, where artistic, business and academic women can spend time to work on projects.[16]

Judy Chicago’s large-scale art piece The Dinner Party awards Hypatia a place-setting.[162] Major works of twentieth century literature contain references to Hypatia,[16] including Marcel Proust’s stories “Madame Swann At Home” and “Within a Budding Grove” from In Search of Lost Time, and Iain Pears’s The Dream of Scipio.[16]

21st century[edit]

Hypatia’s life continues to be fictionalized by authors in many countries and languages.[16] In Umberto Eco’s 2002 novel Baudolino, Hypatia is a beautiful and intelligent woman with pale skin and blonde hair, whom the main character falls passionately in love with and attempts to seduce,[16] but is surprised to discover that she has goat-legs and is half-satyr.[16] Charlotte Kramer’s 2006 novel Holy Murder: the Death of Hypatia of Alexandria portrays Cyril as an archetypal villain without an ounce of good.[16] Hypatia is repeatedly described as brilliant and beloved[16] and she humiliates Cyril by demonstrating that she knows more about the Christian scriptures than he does.[16] Ki Longfellow’s novel Flow Down Like Silver (2009) invents an elaborate backstory for why Hypatia first started teaching.[16] Youssef Ziedan’s novel Azazeel (2012) describes Hypatia’s brutal murder through the eyes of the monk Hypa, who witnesses the incident.[16] In The Plot to Save Socrates (2006) by Paul Levinson and its sequel Unburning Alexandria (novelette, 2008; novel 2013), Hypatia turns out to have been a time-traveler from the twenty-first century United States.[163][164][165]

The 2009 movie Agora, directed by Alejandro Amenábar and starring Rachel Weisz as Hypatia, is a heavily fictionalized dramatization of Hypatia’s final years.[161][166] The film, which was intended to criticize contemporary Christian fundamentalism,[167] has had wide-ranging impact on the popular conception of Hypatia.[166] Unlike previous fictional adaptations, Agora emphasizes Hypatia’s astronomical and mechanical studies rather than her philosophy, portraying her as “less Plato than Copernicus”.[166] It also, more than any other previous portrayal, emphasizes the restrictions imposed on women by the early Christian church.[168] In one scene, Hypatia is sexually assaulted by one of her father’s slaves, who has recently converted to Christianity,[169] and, in another scene, Cyril reads a verse from 1 Timothy 2:8-12 forbidding women from teaching.[169] Near the end of the film, Synesius warns Orestes that he must abandon his friendship with Hypatia in order to retain his faith as a Christian.[169] The film also portrays Cyril and his monks as swarthy, bearded men with covered heads clad in tattered black clothing,[169] resembling media portrayals of the Taliban.[169]

The film, however, also contains numerous historical inaccuracies:[161][169] It wildly inflates Hypatia’s achievements[107] and incorrectly portrays her as having discovered proof to support Aristarchus of Samos’s heliocentric model of the universe,[107] for which there is no evidence that Hypatia ever even studied.[107] It also contains a scene based on the final episode from Carl Sagan’s Cosmos in which Christians burn the “Great Library of Alexandria”, once again ignoring the historical reality that that library no longer existed during Hypatia’s lifetime.[161] The film also strongly implies that Hypatia is an atheist,[107] a notion directly contradictory to the surviving sources,[107] which all portray her as a devoted follower of the teachings of Plotinus, who taught that the goal of philosophy was “a mystical union with the divine.”[107] The film also misrepresents Hypatia’s age;[170] she is thought to have been in her 50s or 60s at the time of her death,[170] but Agora portrays her as a young woman.[170]